Looking back on my life, I realize how extraordinarily lucky I have been. I came to what was to become the central theme of my artist’s lífe at exactly the right time, and I am leaving it at exactly the right time – when it, and I, are no longer available to one another.

These nurseries for critically ill and premature newborns were well established worldwide by the 1960s, and more and earlier premature babies, even some so young as to overlap late abortions, were being saved.

Prior to the 1980s the very idea of drawing there had not been considered. They were carefully closed to other than staff and parents – and even then, parents had at first very limited access.

The history of the incubator is short: it was invented in 1860 and in Victorian times became a fairground attraction – people could pay to file past and see the babies behind windows. It was a freak show, the way the Dionne Quints (almost exactly my generation) and other unusual human beings were exploited and exposed – and when this period was over, strict privacy set in.

From 1983 and for over 3 decades I have enjoyed an inexhaustible drawing subject, that has absorbed my attention through all my mature working life. I began at exactly the right time – I would not have had access before – and I finished at the right time too, when the subject is no longer available. Which coincides with my vision failing in old age. I could not have been luckier.

I lived on Bornholm in Denmark and made a living teaching drawing and doing small portraits, mostly of German tourist children. People started bringing babies for portraits and wanted to learn how. I applied to the hospital maternity ward for subjects to study but was turned down. Someone suggested a Neonatal Nursery, or NICU (Neonatal Intensive Care Unit), terms I had never heard of, but an enquiry to the one in Copenhagen’s Rigshospital was turned down too. That year I was in Vancouver for a longer stay and contacted Childrens’ Hospital there – and was persistent. It took about 3 months to get to an interview with the Supervisor, who was very hostile, but after we met, and talked together about her concerns, she agreed – and later became completely supportive, so I returned on several subsequent visits. After my book Drawings from the Newborn was published, it was easier and I could draw in hospitals worldwide.

I also needed parental permission, and we worked out some changes on their photography permission form, a procedure that has worked till last year in all the hospitals where I have drawn. This was an ongoing study project and I kept the drawings, making copies for the parents in return for permission to draw, keep, and exhibit the originals.

From my initiation to the NICU I was hooked, and hooked forever. Imagine a drawing project that satisfied my every need as an artist, suddenly handed to me.

First and foremost, a new human subject. Drawing people has always been my specialty but I was bored – doing portraits for money was like being a prostitute and having to satisfy the customer, and I suddenly admitted how I hated it, and quit. I taught and still teach life drawing, but the adult models’ poses however inventive were boring, the forms and movements so familiar they were hard to pay attention to anymore.

These babies had never been drawn before because they were not around to be drawn.

I had to start from scratch and I realized very soon how much we draw with our learning and expectations – by our immersion in the culture, by looking at other great drawings. The great artists did not have this subject. Learning to draw these babies took all my attention.

Second, light. There has been uninterrupted, bright light in NICUs till very lately. Staff depended on watching the babies till very lately; machines and warning noises only gradually took over continuous physical supervision.

Third, I had no choices to make. I had to draw the babies I was allowed to, just as they happened to be. And I had no choice over the time I had. I just arrived and got to it; I need not even think. No energy wasted deciding what to draw or how long I had. Or whether to sit or stand – I had to stand. There were changes, interruptions – some permanent. I was happy within the freedom of these limitations.

Lastly, privacy. For me a great part of the joy I have in drawing is that it has been private, I have gotten into places I never would have experienced otherwise, come close to and witnessed human experience that is secret and fleeting, that takes close observation and sometimes was so difficult that my attention was all that was left; in the words of Rilke, the work absorbed every feeling, everything personal “so there was no residue.” This is how it was in the 80s in Palestine when no press photographers or journalists were yet there, how it was on the pediatric cancer wards, in the refugee camps, on maternity wards where I drew childbirth, in the courts (where photography is still not allowed), backstage at great theatres, in a hospital morgue or at the death of a child.

And here too, as if on cue, my privacy is mow invaded too, as documentary filming and “reality shows” have moved in and taken over the most private areas of human experience.

My initiation to the NICU was – as it must be for suddenly affected parents – frightening and alien, not understood, crowded with machinery under bright light, busy with invasive procedures and unknown purpose. Like them, my first impression was of a cold, surgically sterile place; then came my surprise, my realization of the humanity, warmth and care of everyone who worked there.

I drew at night, when the ward was quietest, going in about 11PM and leaving at 3AM. Mostly biking over to Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen, where I drew every night for many years. And in other hospitals in Europe, America, and the Middle East – wherever I could arrange for 2 or 3 weeks’ uninterrupted work. Staff everywhere were interested and supportive. In some hospitals, I slept on the ward when a staff bed was unused. I drew in the basement of the Panum Institute where, in a great vat, lay many tiny corpses.

I made clay models on the development of the foetal face, and drew them from many angles, because it worked better by far to learn emerging facial details than to “think backwards” from our common knowledge of fullborns and children. I knew, all the while, that what I had to get right was visual – nurses can tell at a glance a baby’s gestational age, almost to the day, and if they could see it, surely I could too – but the history of European art is a long tale of trial and error and learning from those who went before, specially as it has to do with the human face.

We read how Cimabue’s paintings were carried through the streets in praise of their exactness, and how they seem to us now stilted and ‘Byzantine’, like this baby at Meteora, and how it took the greater artist Giotto to make that leap, from Cimabue’s shoulders, into the first realism.

For some reason, babies lost out in this timeline. We have all remarked on the adult-looking babies in the Adoration paintings of the Renaissance. The infant Christ was also God and portrayed as magisterial rather than frail.

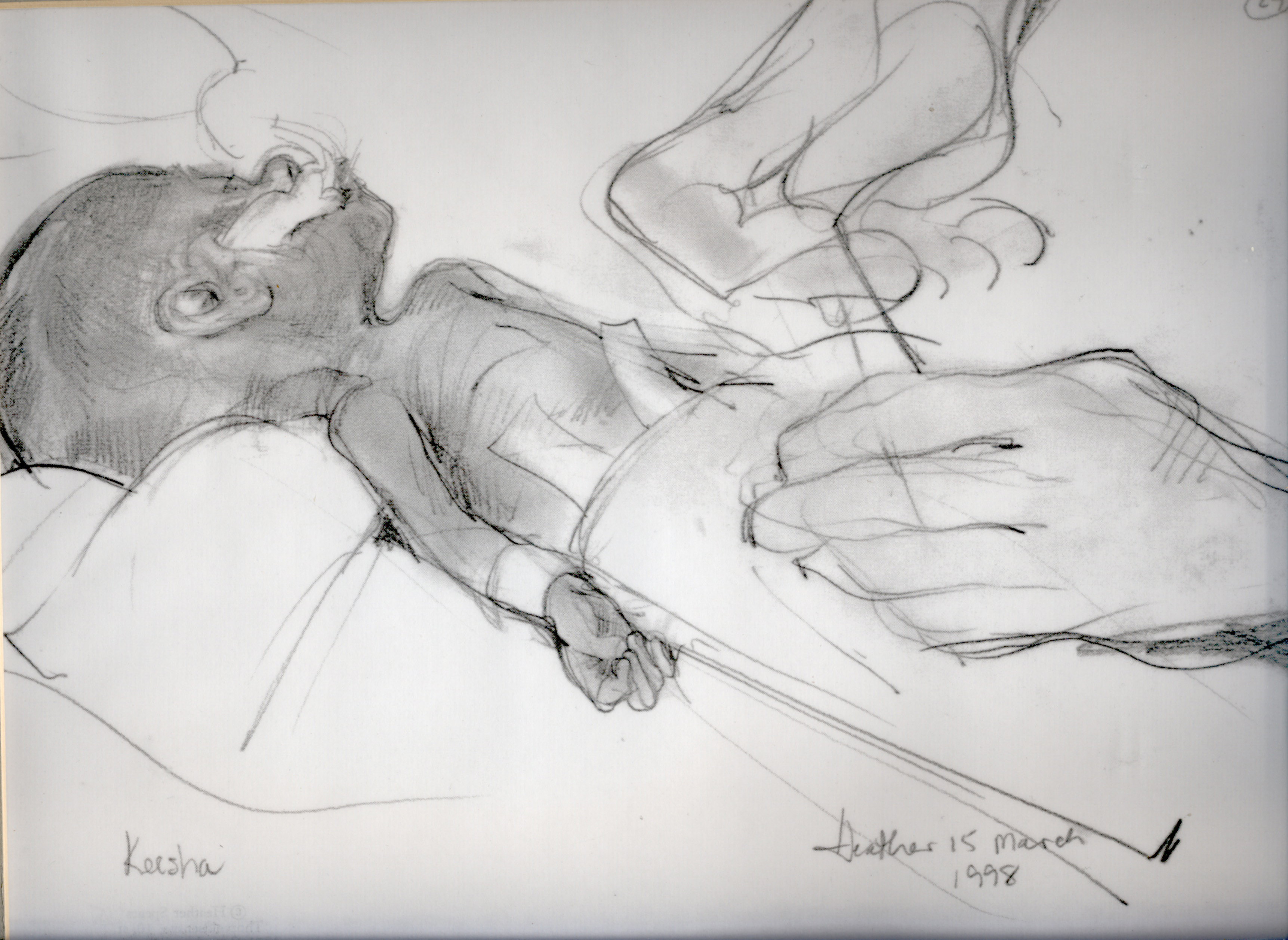

Here are some examples of babies drawn at night on the NICUs. Link to more.

Before ugly plastic took over, I was able to draw the beautiful cotton diapers, and I still mourn their passing.

Incubators changed too – when I began to draw them, they had beautiful linen windows with drawstring sleeves. Staff could access the babies – and, rarely then – parents with strict permission could reach in and touch them.

I drew many hundreds of studies of premature movement, so loose and graceful, different from any human movement that had been around to be observed and drawn before.

So I drew as long as I could. There would be changes, some long overdue.

With the NICUs, more and more premature babies lived, and it was accepted that some would be handicapped, and that some survived to be blind. Continuous exposure to bright light was a connection slow to be made – but it finally was: lights were dimmed on the wards and blankets laid across the incubators. If the baby was being held by its mother, she’d shade its eyes carefully with her hand, and eventually, the time came when to ask for ‘more light to draw by’ was met with reluctance and at best a slight turning up of a distant lamp. Meanwhile as if on cue, a bout of shingles 2 years ago had damaged my one eye, and my vision will never be whole again: all in all, it was time, it was necessary, to stop.

The incubator will be phased out, replaced more and more by warm, sterile rooms where the parents are happy to live in, touch, hold and care for their babies. Years ago they were lucky to be allowed visiting hours, and even, for a moment, to touch their baby through a carefully opened incubator door. Later they were thankful to be allowed to come in when they liked, and to sit with the baby, lines dangling, for longer periods skin to skin.

But the incubator is also called an “isolette”- and isolation is finally acknowledged to be far more dangerous than any risk of infection.

I still draw if I am called in by the midwives – if a baby is stillborn and they judge the parents could bear to make a decision and let me draw a picture for them. And in the chilly side room off Maternity, there is still light.

Hi Heather, just finally up and running with my computer, and WordPress… hope this translates, as I really enjoyed your story of your life in drawing, and really just want to say .. how wonderful for you that you are able to delineate the beginning and ending of your work, and to sound so satisfied with the gift it was to you, and continues to be, and the gifts you created for so many through it. The photographs and video go beyond words for me… delicate, sensitive, beautiful, all of that, but you capture an essence of something far deeper, the simple truth of who each child is/was… a truth that for me, feels like a whisper, it’s so personal…. Dina E Cox

LikeLike

Magical…and so on target. Thank heaven things have changed in the NICU. Very moving!

LikeLike

thank you Jean so glad this reached you

LikeLike

Oh, Heather, what a beautiful piece! So glad you wrote this and with the drawings!

I think this is where I reply. Lovely to see this just after I sent off my letter to for your approval. Than you. Pls hit Follow somewhere or other

LikeLike

Thank you for this insightful post on how an artist comes together with the historical moment — and how that leads to seeing something we haven’t seen (or perhaps just haven’t looked at) before.

LikeLike

glad you found it and liked it!

LikeLike

Thank you Heather for your reflections, for your powers of observation, sensitivity, and perseverance. I love how you understand things from inside out and glad you recorded your journey. I am glad you were there at the right time to record, observe and connect with babies, parents and staff. Bringing the human touch enhances connection and communication. Babies are sensing and feeling from a very early age and you are a front runner in understanding an important phase of our human development. You have been able to articulate, observe and visualize an experience where there are initially few words. The pre and perinatal psychology folks believe we replay our birth and newborn experience in our life. I am touched by your observations with the movements of faces,hands and bodies. Your process and your visual images and that you shared are in movement and flow. Your dedication to the art and science of the newborn is amazing. As a premature infant and in an incubator for 2 months, I am glad for the changes especially with skin to skin contact and increased parental involvement. It is amazing that incubators and bright lights have had such a long run with little reasearch and how we run with a “good idea”. Also let the readers know about your book of newborn drawings, I treasure and share with parents.

In appreciation, for your journey and you artistic offerings, thank you.

Catherine Fraser

nurse,artist,art therapist

LikeLike

thanks so much Cahterine – you are right I should name the book aaslo that it was a big hrlp in getting permision to draw. write soon love Heather

LikeLike